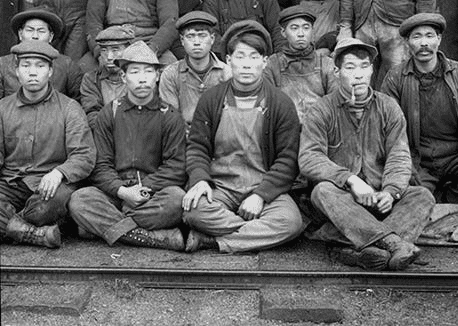

For centuries, Asian Americans faced the harsh reality of racial discrimination. This escalated significantly with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first federal law to ban immigration based on ethnicity. These new restrictions made it incredibly difficult for Chinese immigrants to build a life in the United States. You can read more about this on dallas1.one.

The struggle extended to education, making it challenging for Asian Americans to access proper learning opportunities. However, Dallas boasts a unique history of adapting its educational systems and integrating diverse cultures.

Asian Americans in Dallas

J.L. Chow was the first person of Chinese descent listed in the Dallas directory. In 1873, he moved into the Central Hotel, and just a year later, he opened his own laundry on Elm Street, aptly named Chow Chow Laundry. Following a strike at the Houston and Texas Central Railway, more Chinese immigrants arrived in the city. They typically came to Dallas to earn money on the railroad, hoping to eventually open their own businesses. By 1886, Dallas was home to 15 Chinese laundries.

By 1900, only four laundries remained, with other Chinese businesses primarily consisting of grocery stores and restaurants. A decade later, in 1910, Dallas had just three Chinese restaurants, and Chinese immigrants no longer owned even the grocery stores. The number of their businesses steadily declined.

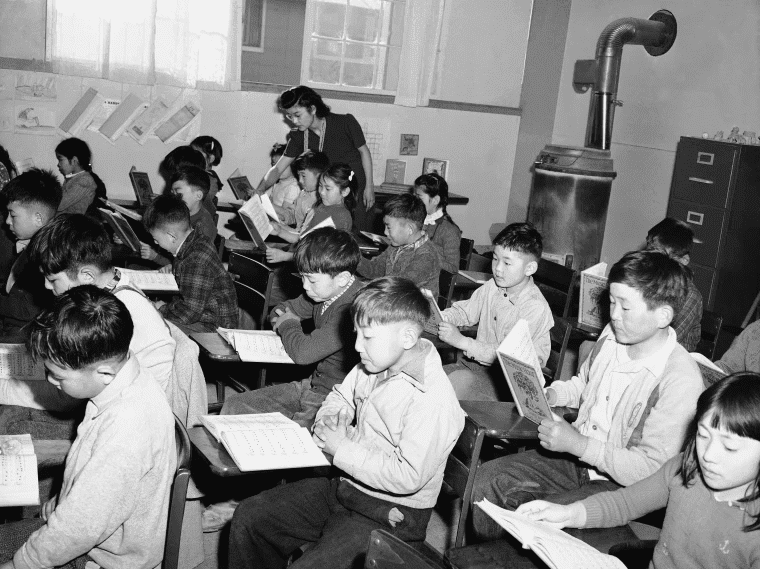

Integrating Asian Americans into the Educational Process

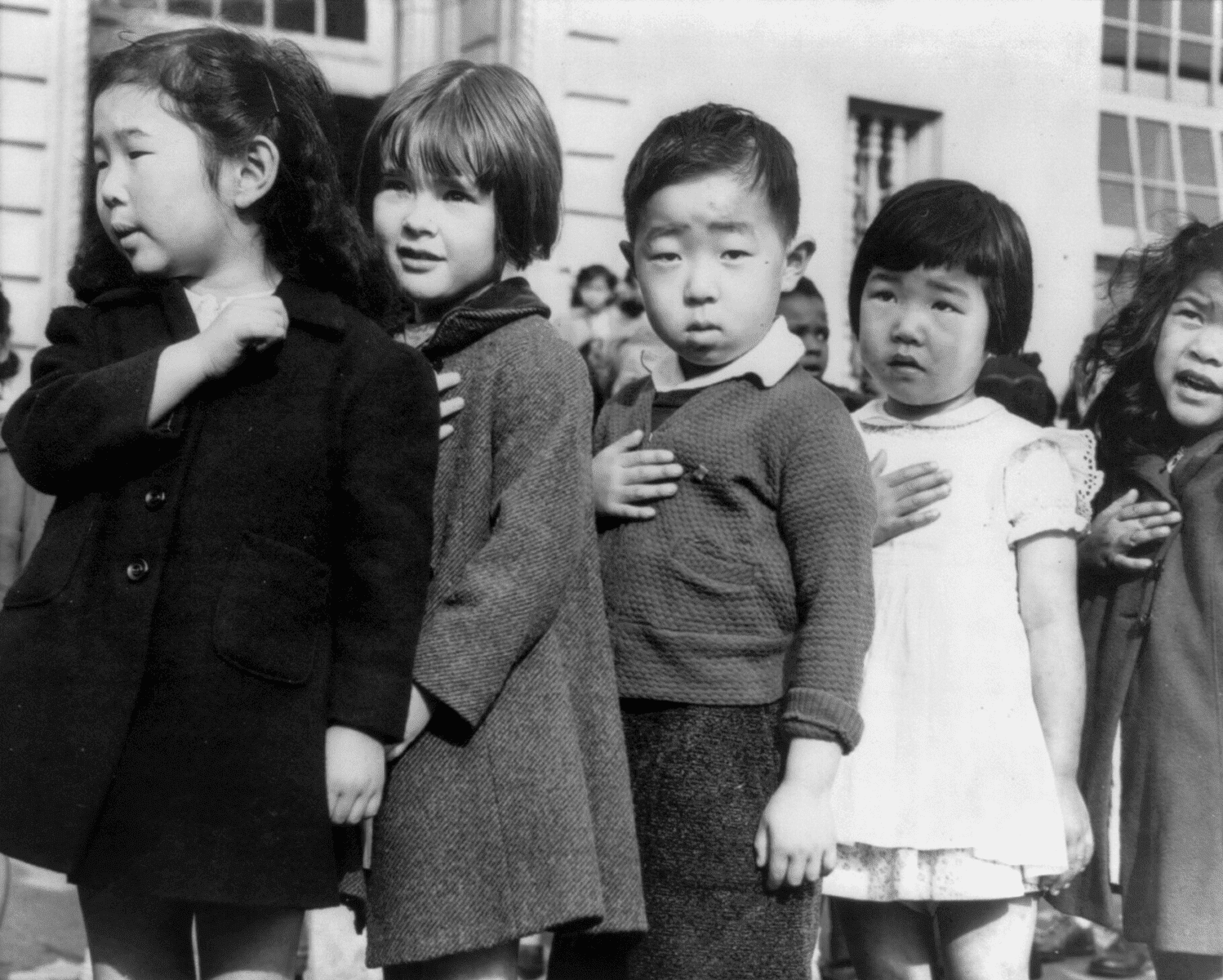

A pivotal moment in American education was the inclusion of women and ethnic minorities. Each group carved its own path to learning. For women, gaining basic education was paramount, as college attendance was rare at the time. However, as higher education gained importance, educators actively worked to overcome gender imbalances in colleges. For ethnic minorities, particularly Asian Americans, the situation remained more complex for a long time.

Amidst turmoil in Asia, some Chinese immigrants defied the emigration ban and sailed to America. Conflicts in their homeland fueled tensions between Chinese and Japanese Americans. This prompted American educators to develop specialized approaches to educate each of these minority groups.

In Dallas, educators focused on ensuring equal opportunities for Chinese and Japanese individuals, whose societal standing was often precarious due to historical and political circumstances. Special support programs were developed, including language classes and cultural evenings where they could showcase their traditions and customs.

Quality Education: An Indispensable Part of the American Dream

Before the 1960s, relatively few people from Asia immigrated to the United States. While information varies across sources, they likely constituted around 5% or even less of the total immigrant flow. Chinese immigrants began arriving in the U.S. in the 1850s, followed by Japanese immigrants in the 1880s. Filipinos arrived in America in very small groups until 1900.

These immigrant groups significantly differed from others in their socioeconomic status. This is evident in the fact that almost all Asian immigrants residing in Dallas owned food establishments. Most Chinese and Japanese immigrants belonged to the middle or upper class. Due to their status and sound financial standing, these newcomers had a strong interest in quality education. For Asian Americans, education became a crucial factor in achieving the American Dream. And while they fully recognized the importance of education, their journey had its own unique characteristics. They were more proactive than European immigrants in advocating for the creation of special schools to preserve their culture.

In some Texas cities, Chinese immigrants established their own schools to preserve their culture, while Japanese immigrants opened educational institutions where they taught their language and traditions. This marked the first step toward maintaining their cultural identity while integrating into American society. However, in Dallas, members of these national minorities were long limited to language courses and cultural events. Due to their small numbers in the city, there was little reason to establish separate educational institutions.

Early Educational Programs Tailored for Asian Americans

In 1991, the Plano Independent School District launched a Chinese bilingual program for preschoolers and kindergarteners. This program was developed by Donna Lam after Chinese professionals began settling in larger numbers near Dallas, in Plano. At that time, most Asian American families decided that English, Chinese, and mathematics would be the most important subjects for their children.

Donna Lam’s program became a vital part of the educational process for children who had moved to the United States at a young age. It helped children who didn’t yet speak English adapt better to the American education system. The program aimed to enable children to learn two languages simultaneously. This was crucial for Chinese children who lacked opportunities to practice English at home.

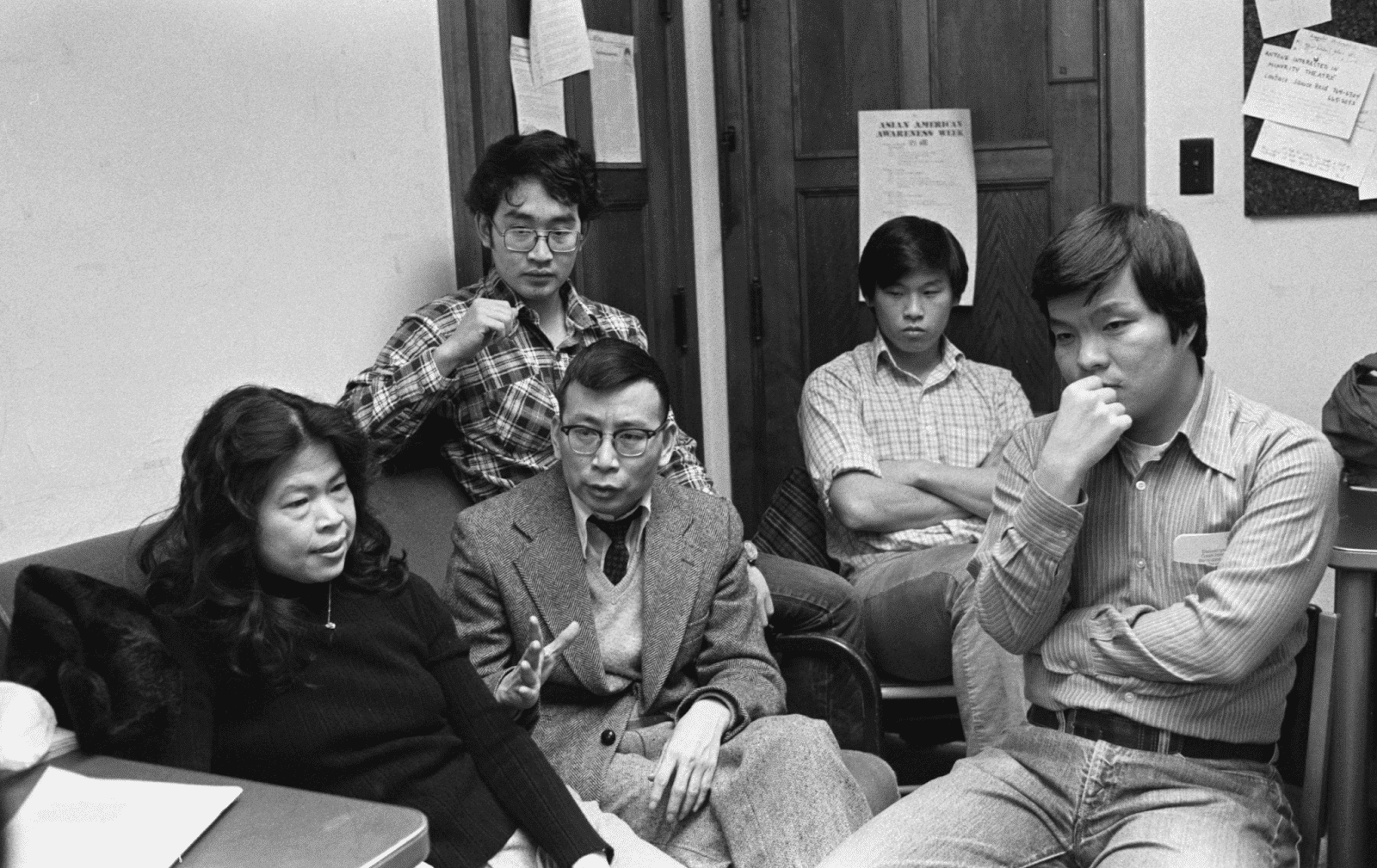

The University of Texas at Dallas was the first higher education institution to enthusiastically adapt its programs to meet the needs of this minority group. In 2012, nearly 1,000 students of Chinese descent were enrolled at the university. This was primarily due to the university’s dedicated efforts to recruit students from China.

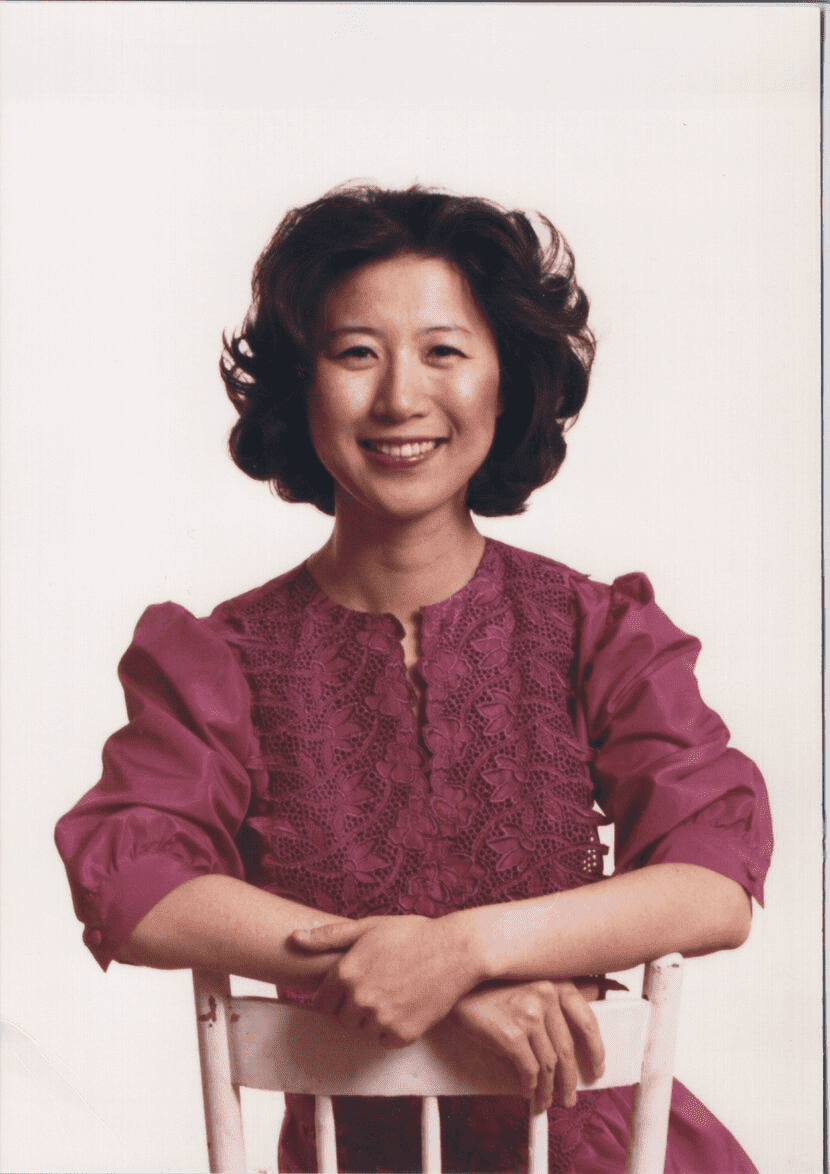

Suzanne Insook Ahn: An Asian American Educated at UT Southwestern

Suzanne Insook Ahn was born in Busan, Korea, in 1952. At the age of seven, she immigrated to the United States with her parents.

Dallas was the city that provided Suzanne with an exceptional higher education. She graduated from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and worked as a neuropathologist for many years. She rarely spoke about her academic journey, so it’s unknown whether she faced discrimination due to her heritage. Nevertheless, for various reasons, Suzanne Insook Ahn actively participated in the city’s civic life, advocating for the rights of Asian Americans.

In 1989, she helped found the Dallas Summit, whose main goal was to ensure Dallas women had sufficient rights. Additionally, in 2003, she donated $100,000 to the Asian American Journalists Association to amplify the influence of Asian Americans within the broader community.

The story of Suzanne Insook Ahn, an educated and determined Asian American, became the catalyst for establishing the Dallas Asian American Historical Society. This society serves as a place to preserve the memory of immigrants who contributed to the development of Dallas and the United States as a whole.

Sources: